Published John Wiley & Sons - 2001

These essays have been edited from their published versions

CHAPTER 5 - Architecture ::

Alan Balfour

New York City is for the most part an art-less place. Art-less for good reason because, apart from the cost of making architecture, using it to reflect symbols and signs of significance in communities that are in constant flux is simply misplaced. In a more compound sense, there is no relation between creating the physical shells that embody a refined set of values enjoyed by a cultural elite - which is the way in which architecture increasingly defines its experimental role - and the needs of neighbourhoods and communities under the strain of relentless cultural adjustment. The results would be at best foolish, at worst an interference with the necessary open-mindedness that such a social transition requires. This transition would seem to be best served by an architecture of modesty and anonymity, one that is light on the ground, able to adjust. Seeking permanence through architecture is simply inappropriate in the culture which thrives on continual change, in which migrant groups seek to establish cultural identity through means that are just as rich as architecture - music and food, rituals and religion - but much less permanent. The European roots of the uses of architecture in America are far removed from the Latino or Afro-American experience. Added to this, most new migrants have little or no cultural connection to the uses and semantic subtleties that infect bourgeois architecture.

Architecture increases the way in which the past weakens and distorts the present. The decay of a neighbourhood is much more painful when the once noble illusions embodied in its architecture are seen to be destroyed. The evidence is everywhere of the folly of attempting to create the illusion of permanence and civic dignity in a society that, with the formation of new communities, is not simply in continuous devolution but is in a state of continual experimentation. It is too seldom acknowledged that America's pluralistic democracy and openness to immigration forces society into a perpetual experiment with the form and structure of community. As waves of migrations move into Brooklyn, the Bronx and Queens no attempt is made to manage their impact on existing communities, to actively direct the process of cultural reformation, and no serious consideration is given to the social and cultural clash inherent in this process. Tolerance of open and unconstrained migration makes the United States utterly distinct, makes America appealing to the world, but the role for architecture within this process has yet to emerge.

Architecture in New York occurs in only three areas of cultural production: the corporations that build to enhance their image; wealthy patrons who glorify their family names by endowing public institutions; and the agencies of government - city, state, federal - that seek ways of signifying public order, and almost all of it takes place on Manhattan. The nature of that production divides, as it does in the pages of the New York Times, into two quite distinct worlds: the art section and the real estate section. In the art section the critic, often with wit and imagination, explores the architectural issues that emerge from what is essentially art practice. This fashionable and ever changing world exists simply to refresh and stimulate interest in the possibilities of property. The real estate section deals with architecture as a much more stable element in the continual construction of that most serious, and again mostly concerned with that highly conservative, project, developing Manhattan.

Columbus Centre

One piece of the grid destroyed by

the Moses regime is being restored. The grid has been continually

successful in limiting the ability of any individual or organisation to

create an excessive presence within the city. There are exceptions of

which the Rockefeller Center the most endearing. In 1929 JD Rockefeller

Junior assumed control of the several blocks in midtown that had been

set aside for the development of a new Metropolitan Opera House. After

the Wall Street Crash he personally took command of the project, which

he believed would provide a civic and moral lesson to the developers of

the city. Though he controlled several blocks Rockefeller at no time

considered closing or diminishing the order of the grid. The greatest

weakening came with the Robert Moses led development of Stuyvesant Town.

In his zealous drive to rid the city of slums Moses gained control of 18

city blocks between 14th and 20th Streets on the East River and removed

all signs of the grid in the construction of an extensive public housing

project. The 42nd Street development, even with the exceptional powers

given by the state control of land, at no point considered closing

streets or interfering with the grid, and nowhere in the present state

of reality is there any desire for the isolated hostile order that was

the World Trade Center. Developer Donald Trump is freed from the grid in

his grim apartment developments along the railways on the Upper West

Side. All such concerns come into play in the proposed development of the Coliseum site at Columbus Circle. Smaller in area than the 42nd Street project - 2.5 million square feet compared with 7 million - the Coliseum was built in the 1950s and made obsolete with the opening of the Jacob K Javits Convention Centre in 1986. Covering and fusing two blocks at the southwest corner of Central Park, the development was once again the result of a Moses attack on the slums that had occupied the site. The land is still owned by the authority that became his main power base: the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority. (The title Coliseum was not a romantic gesture but a direct reflection of the Moses ambition. When opening Shea Stadium several years later he said 'When the Emperor Titus opened the Coliseum in 80 AD he could have felt no happier.' However, belying its' name, the Moses Coliseum was a work of dismal mediocrity.)

After many years of false starts a project has finally been given initial approval in an intricate waltz between public and private interests. Some knowledge of the process gives an insight not only into the forces that constrain development in the city, but also into the specific way they shape the architecture. Boston Properties were the first to attempt to develop the area with designs from the Canadian architect Moshe Safdie. These failed to find approval because they were seen as failing to respect zoning constraints - the developers proposed a volume 18 times the area of the site, while zoning allowed only 15. Greed was mentioned in turning down the application. However, it was also felt that the mass of the building would have cast lengthy shadows across Central Park and that it was therefore unacceptable. The architecture of the Safdie proposal can be seen as a mannered work of Modernism that gains its character through crystalline forms. At this point Boston Properties switched architects, from Safdie to David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). Childs, (who dignified the memory of Check Point Charley in Berlin,) produced a more conventional development that respected the limits of zoning. However, weakness in the New York economy at the end of the 1980s, and persistent opposition on environmental grounds, put the project on hold. Boston Properties finally withdrew in 1994.

The following two years were marked by a power struggle between the public owners of the site and the new city administration under Mayor Giuliani and Joseph Rose. In July 1996 the authority issued a public request for proposals to develop the site. There were specific design guidelines, not unlike those developed for 42nd Street, but the desire here was for unity. One instruction was very clear: the street Moses had closed over should be visually reopened and 'a view corridor' that would follow the line of Central Park South through the site was required. Gaining the maximum usable space from the site mandated two towers whose height the guidelines limited to 750 feet. The proposal process led to a two-phase competition with five submissions in the final stage. (To give some insight into the relative significance of architects versus developers, each designed submission was illustrated in a half-page article in the New York Times with no mention of the architects.) The architects who prepared the final five submissions were Kohn Pedersen Fox, Helmut Jahn, Robert AM Stern, David Childs of SOM and James Stewart Polshek. The architecture was varied. Some dressed the buildings in the range of mannered geometries that had characterised the Safdie designs. Polshek, Stern and David Childs offered varying degrees of what might be called historicised contextualism, though in quite a mild form, the effect of which would maintain the character of the streets surrounding Columbus Circle.

The struggles that followed between developers and the agencies of the city presented what is perhaps an extreme example of the unpredictability, the almost Darwinian character, of the city's evolution, but one that is typical. In 1997 many felt that the project would go to the developer who already had several successful ventures in the area. The mayor's office was not happy, partly, it was said, because of the developer's overriding wish for profit, but also because, in the mayor's view, the project lacked a suitable public element. Specifically - the development lacked a public theatre. Commissioner Rose commented, 'We were never trying to design the buildings for the architects, we were trying to incorporate values into the project.' The public element, it was quickly agreed, would be a new home for Jazz@Lincoln Center, a popular performance programme directed by trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. All this evolved as the many interested parties pushed to gain the most for their agendas.

At this time Columbus Center Partners went looking for a major tenant who could add a strong name, and at best a brand name, to their package and after a chance or planned introduction to the president of Time Warner invited the company's participation. After several months of reflection Time Warner agreed to join with Columbus Center Partners in developing the site. The partners offered the mayor's office a proposal that would house the world headquarters of People magazine and Sports Illustrated - and, in a jewel-like setting high above the circle, the stage for Jazz@Lincoln Center. The city's decision to go with Columbus Center Partners was made in July 1998. David Childs directs a team that involves many designers, including Rafael Vi–oly who is creating the performance space for Jazz@Lincoln Center.

The evolution of the project illustrates the resiliency necessary both to practise and configure architecture in New York City. All the major elements of the building were predetermined. The massing was a product of an exacting relationship between the zoning ordinances and guidelines added by the city and the developer's need to maximise profitability in all parts of the project. This includes the success of the retail stores, the attractiveness of the performance spaces and the ability to attract powerful tenants. The retail areas on the street level will complete the curve of Columbus Circle and the building will be entered through a grand atrium, on an axis with Central Park South that carries high above the street the performance space for Jazz@Lincoln Center. The continuation of the grid through the site makes the cut between the two towers, which are held well back on the site to avoid overshadowing the park and to maintain the scale of the buildings around Columbus Circle. Their geometry is created from the trapezium formed between the city grid and the diagonal path of Broadway. The focus of the view down Central Park South will be the cascading glass roof of Jazz@Lincoln Center.

Though a singular and united composition, the Columbus Center is arranged with elegant artifice. The dramatic scenography takes advantage of a site that gains great spatial freedom by being at the circle and on the park. The crowds on the streets will be aware of layer upon receding layer, shifting from the circle through several planes to the crested towers whose final form, brilliantly lit according to Mr Childs, will owe some debt to the Chrysler building. The design makes no direct use of historical elements in its general accommodation to the existing form of the city, and its subtle modulations give it a presence sympathetic to the great work of the 1920s Rockefeller Center. In Space, Time, and Architecture the German theorist Siegfried Gideon saw in the patterns of the buildings that surround the RCA tower a natural representation of the dynamics of space and time that he felt would mark the 20th century. Similarly, the effect of the rhythmic modulations to the mass of Columbus Center is to create an implied vortex spinning around the figure of Jazz@Lincoln Center, but this is more apparent than real. There are no reflections of uncertainty, no flirting with fashionable chaos here. Columbus Circle in the new century will present confidence and clear order.

As architecture becomes a minor branch of media and often co-opted by its more powerful rivals in advertising, prestige products will by necessity become the measure again which architectural significance is measured. This might consider buildings as bodies and their surfaces as dress and find fashion equivalents for the manners of various architects. The SOM project for Columbus Center might be viewed as being in the culture of, say, Brooks Brothers or Sack's, MoMA in the spirit of Armani or DKNY (not quite dangerous enough for Prada), and Times Square explicitly Disney with a touch of K Mart. It is possible to recognise a convergence between the increasing influence of corporate design on all life-style artefacts so that trademarked reality is displacing individual imaginations. Objects shaped by individuals have an authenticity, if only because subjectivity is absent in objects and places defined by corporations. Such dressings are merely comforting masks on the face of the city, gently seducing with empty promises.

Rival Towers

There are several other new

towers close to Columbus Circle. Helmut Jahn, whose work over the years

has been marked by strong clear forms and order, struggles to give

coherence to the City Spire development. This appears to be an example,

and there are others, in which the developer's need to maximise every

square foot of space makes the formation of coherent architecture

impossible. Immediately to the west, the development of luxury

apartments above Carnegie Hall illustrates the difference when the

architecture is guided by formal principle and not by optimal use. Cesar

Pelli has formed an exquisitely elegant wafer of a building, its brick

facade textured to be in sympathy with Carnegie Hall. It rises above the

complex bulk of the hall forming an elegant curtain that floats within

the city. The effect is of an almost tapestry-like backdrop to the great

mass of the hall and its simplicity and equanimity give it an authority

that diminishes all its neighbours. All these are products of client desire and the need for profit. A work by Kevin Roche, 750 Seventh Avenue, chooses to be wrapped in shiny black glass and its ungainly bulk overwhelms any attempt at architecture. The crowning spire attracts too much attention to a building that would have been best left to lose itself to the messy collage that is the perceived city. In comparison the Regal Hotel design by Roche and Dinkeloo, close to the United Nations building, has a simple form wrapped in an elegant curtain of glass. Roche and his partner John Dinkeloo designed what still remains one of the great works of Manhattan architecture: the Ford Foundation building. The comparison with 750 Seventh Avenue is obvious. The Ford Foundation required a work of architecture that would embody the distinction and public character of the foundation. This public dimension led to the creation of an internal garden and the internal relationship between the activities of the foundation and the city has never been repeated. That the same architects are unable to give so little to a task that is explicitly concerned with optimal exploitation of space reflects the constraints of Manhattan, not the limitations of the architects.

For an observable evolution in the design of facades compare the SOM Bertelsmann tower of 1989 with several recent and proposed projects. Each particular volume that forms the Bertelsmann building is given a distinct surface treatment, there is rather crude patterning of windows and panels and the elevation on to Seventh Avenue is given a prow which is capped with a spire that rivals that on the Roche building to the north. In recent projects this kind of piecemeal, rather graphic, formulation has evolved into much more refined public presence and manufacture. The soaring, almost freestanding, tower designed by SOM for Times Square will overwhelm the buildings at the apex of Broadway and Seventh Avenue, its southern facade carrying advertising more than 1,500 feet above the square. Compared with the Bertelsmann building the surfaces comprise a fine weave of softly muted green glass shot through with diagonal patterns that define the angle of the roof edge. (f.28) Over 700 feet high, it will share with its neighbours 100 feet of advertising space at its base as well as a vertical billboard.

The subtle diagonal inflections on the surface of the Times Square project become embedded in the complex of three-dimensional geometries that defines the shell of the addition to 350 Madison Avenue, from SOM. By far the most experimental project in the commercial centre (and one untouched by Columbia's complexity theories), it is formed to a geometrically complex box that rises from the masonry of the existing building. Its surface, initially a dense mesh, is now an exquisitely modulated curtain wall, its harmonics influenced by the poetic structures of Ellsworth Kelly. It creates the effect of a tense metal plane shafting out to the existing building and projecting back across a 20-foot gap in the block before surrounding the glass volume of the new office space. The most striking effect will be at the entrance into the glowing mass of space formed in the gap and sustained by a combination of light and steam reaching the full height of the building. The way this effect penetrates the block is quite new in the city. Alone among recent commercial constructions, 350 Madison Avenue suggests that there are possibilities for new orders to be explored, and new pleasures to be enjoyed, by developing effect within the depth of the block. The subtlety and complexity of this work suggest that theoretical practice stimulates mainstream practice, but architects will not acknowledge this.

This increasing refinement in the design and technology of the city's commercial architecture emerges from two parallel influences. Among the most status-conscious clients, of which New York has a few, fresh invention enhances reputation. However, developer clients in particular match style with the marketplace and within this process architects are required to produce numerous iterations of a design until form matches client desire. Unlike much of European practice, the architect's personality is suppressed within this process. The context within which architecture is perceived in Manhattan is unique: part of the grid wall at the base, limited freedom above the 12th floor, the only internal articulation in the lobby and perhaps the penthouse. This pattern of constraints frames a very specific set of New York design problems, central among them the character of the facade, which has been an issue in the city since the turn of the century. The architects for Rockefeller Center described the problem as being similar to that of designing a tapestry wall hanging and produced numerous renderings to discover the most satisfying effect. 'Vertical garden' was another metaphor to colour the imagination. This is a highly subjective process and there is no clear objective measure of effectiveness. The use of computers has affected all aspects of practice in the last decade and has been especially effective in supporting tasks that require countless iterations. It is a process in which the technology must match the effect. It is this constrained New York context that drives the reordering of the volumes and surfaces of commercial architecture and has gained such worldwide influence.

The reserve with which New York practitioners work within the grid is not shared by foreign architects when they practice in the city. (As an aside, the essentially pragmatic needs of New York culture have meant that very few have been invited to design here.) For the New York architect, making a facade interesting is little more complex than designing wallpaper. Europeans take a much noisier and more figural view of architecture.

Two recent projects inserted into the grid by European architects were commissioned by European clients. The Parisian practice of Christian de Portzamparc has formed a small infill building for the fashion house of Louis Vuitton. A loft building in a gap-site, its only architecture lies in the fracturing of the facade into complex layers, wasting space in ways that would seem irresponsible to New York developers. It gives a moment from the anxiety of French philosophy to the pragmatic face of the city. A different but equally foreign facade has been given to the Austrian Cultural Center by the Austrian architect Raimund Abraham. Abraham is in truth as American as he's Austrian, having lived and taught in New York for many years, but his strong symmetrical modelling of the street forms a distinct presence and has faint echoes of a younger Abraham whose powerful drawings touched worldwide desire. These projects are interesting in only one respect they show New York does one share the poetic pleasure in the aesthetics of technology that characterises the best of European architecture. Though pragmatic, American architecture rarely elevates or fetishises the materials of production. European architects argue that allowing necessary technology to determine the language of the architecture avoids contrived effects and artifice and gives an unambiguous truth to the objects of reality. In the United States, however, though there is an oppressive use of architecture to support commercial display, the buildings themselves represent a neutral undemonstrative use of technology.

The density of the grid continually frustrates the assertion of difference. In all its confusion of textures and chaos and layerings and neglect, any such attempt is simply one moment in a kaleidoscope of enterprising fragments. Buildings are never seen as individual but as constantly changing layers within the walls that contain the grid of streets. The space between the walls frames the public life of the city. The experience is dominated by traffic. Because all servicing is from the streets, mainly the cross streets, it is impossible at any time of day, or even night, to avoid delivery trucks and carts and trolleys and produce - vegetables, dresses, filing cabinets. All the equipment of life seems to be in constant motion around the city. Every journey involves stepping around the delivery man, always into the path of cabs and limos. Throughout the midtown the dry oily air is softened by the sour steam rising from the street vents, adding piquancy to the sugared candies and roast kebabs on the pans and grills of the street vendors.

Architecture struggles for position in the great walls of buildings formed by the grid. It is not a subject of much interest and the grid is a great leveller - as it was intended to be. Subtle differences in style become insignificant in the dense sandwich of the city block. There is an awareness of entrances and shop windows and a pleasant sense that, although public life is here on the street, all buildings are in some way accessible. At ground level the presence of architecture is most keenly felt at the entrance lobbies to buildings grand and grim. They establish the type of life and activity within each property. Yet the grid enforces not just conformity but a grudging egalitarianism. From boutiques and the department stores that line Fifth Avenue to the sleaze joints that have been forced to the edges of Eighth and Ninth, and even to the raunch among the meat packers, some peculiar metaphysics makes them all part of the same play.

The city is a complex stage which shapes behaviour in its own way. The bicycle messengers of New York are the most soulful players on its most dangerous stage. They embody the continual struggle that drives the city, seeming to have no race or culture separate from the role they have chosen to play. Dressed in stylish helmets and filthy jackets; unsmiling, always on the verge of anger; risking their lives, with total disregard, in the waves of traffic. They cannot be paid enough to be exposed to such continual danger - they must do it for the sport. They are the gladiators in this city of unceasing conflict, dying young, among the garbage and street furniture and fenders, for all of us. Back to architecture:

Pennsylvania

Station

In New York City the great railway stations once rivaled

the Museums in grandeur and civic presence. The destruction of

Pennsylvania Station in 1962 has lingered painfully in the memory of the

city. This most monumental of the urban works of McKim, Mead and White

gave New York a series of heroic public spaces of such permanence and

grandeur that it was believed they could last for ever. It was the

arrival point for travellers from across the nation and presented

immediate evidence of the power and strength of the great city. The

noble granite colonnade led to a majestic waiting room and into a

central concourse beneath an intricate series of glass and metal vaults.

The destruction of this most confident work from the first decade of the

century has been kept alive in the photographs of Berenice Abbott. In

the early 1960s the Pennsylvania Railroad decided to demolish the

building. The railway station would remain below ground while the street

level would be developed to produce profits for a major entertainment

venue named Madison Square Garden after the most ambitious of the

turn-of-the-century entertainment buildings, designed by Stanford White.

Despite a highly vocal and well-prepared opposition, strongly supported

by public opinion, the vast monument was demolished and below ground the

Penn Station remained squashed into an insignificant basement lined with

cheap shops and restaurants, with uneasy travellers demeaned by the

setting. The loss of the building has preyed on the memory and

conscience of the city. The failure to prevent its destruction led to

the creation of the Landmarks Preservation Community to ensure that such

actions would not succeed so easily in the future. Penn is the busiest

station in North America with 600,000 passengers daily being forced

through its mean passages. In 1993 the Farely building immediately west of the station was declared redundant. Conceived on a scale equal to that of Pennsylvania Station, it was the most monumental post office on Manhattan and was also designed by McKim, Mead and White, almost contemporarily with their old Penn Station. Soon after the intentions of the US Post Office became public an idea began to take shape: why not re-establish Pennsylvania Station in the Farely building? All the physical elements were in the right place. The post office sat above the tracks that served Penn Station and that were in exact alignment with the trains from north and west. The idea was made visible in the drawings of the architects Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum (HOK), and attracted the attention of the senior senator from New York, David Patrick Moynihan.

As the project advanced HOK lost out to SOM, and a team led once more by David Childs, they produced a design that is a splendid fusion of restoration and spectacular renewal. The broad form of the post office is similar to the old Penn Station: the great stone-encased outer band of rooms surrounds an inner glazed court where the mail was once sorted. There are two halves to the building, with the post office on the east separated from a bulk storage building on the west by a service road. Only the east building would be used, the service road becoming the grand entrance hall to the new station. Although far from being a fait accompli, the idea assumed such compelling rightness that President Clinton chose to lead the unveiling of the proposal in May 1999. He was surrounded by the great and the good of the city with the exception of the mayor - from which it can be deduced that this ambitious project did not have his endorsement. It could just have been politics; city issues championed by the late Democrat Patrick Moynihan could not be allowed to steal the thunder from Republican Mayor Giuliani.

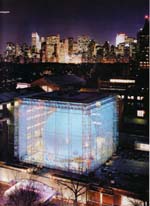

The work of David Childs and his team was never been more confident. The proposal would create the new station around two elements: creating a concourse in place of the service road and transforming the sorting hall into railway platforms. The most spectacular feature would be the new entrance to the concourse. A segment of an imagined sphere, emanating from the centre of the building, defines the geometry for a sweeping shell of glass and steel that would flow between 32nd and 33rd Streets, enclosing the entrance hall and soaring above the mass of the old building. The screen would become a floating, ethereal veil rising high above the classical weight of the post office. The conversion of the sorting hall into the new concourse would retain the old steel trusses but remove the floor to give access to the tracks and trains. The new station cannot be created before the arrival of high-speed trains, and the disaster of Sept 11 diverted attention from all such projects and in march of 200 with the death of Patrick Moynihan the project lost it s most passionate champion.

The shifting pattern of desire that shapes the architecture of New York is the product of many variables. All is made simpler, however, by the overwhelming pragmatism of the process by which it is created. Even the most persuasive theories are marginal in the face of cost-effectiveness. New York is formed first and foremost by investment decisions. Pennsylvania Railroad made money by tearing down the old station. The new station, if built would be created out of necessity not romance, but the arrival of high speed trains in 2000 lgretly enhanced the idea of rail travel.

The restoration of New York's surviving major station, Grand Central Terminal, was completed in 1999. Long overdue, and clearly appropriate to a city that depends so much on train travel, it is a thorough and pleasurable restoration by the architects Beyer Blinder Belle (paid for by the Metropolitan Transit Authority, the building's owners). The great pavilion, which presents a triple triumphant arch to Park Avenue South, houses the main concourse 375 feet long by 125 feet wide. The design was won in competition by Whitney Warren of Warren and Wentmore in 1912. The traffic arrangements, both internally and externally, were laid out by the engineers Reem and Sterm. They not only devised systems to separate all different forms of traffic - subway, pedestrian, automobile - but also created the sensational short highway that loops around and through the building, plunging under great arches on to Park Avenue. It is still one of the best metropolitan experiences in the city. (The upper reaches of Riverside Drive offer similar thrills.)

Grand Central was owned by the Penn Central Railroad in the 1960s and, like Penn Station, was also seen as being exploitable. Plans included inserting several floors into the waiting room to accommodate a variety of activities including a bowling alley. Another proposal was to build a 50-storey tower over the waiting room. Grand Central was declared a landmark in the midst of these exploitive plans. The railroad company sued to have the status lifted but failed.

The BBB restoration lovingly re-creates not only the surfaces but also the sense of grand procession through the halls and passages and over bridges. A new grand stairway and terrace that have been added to the east end of the concourse succeed in making the main concourse feel more powerful and balanced. Viewing the crowds from the terrace bar is to feel that one is at the centre of a great city. The restoration recovered much of the ceiling, which depicts the constellations with the stars picked out in twinkling lights. The recovery of the broad ramps that lead to the lower levels enables one to enjoy a similar but slower pleasure to that of driving along the elevated road that snakes around the outside of the station. With gentle grandeur the great slabs of marble drift easily down to the lower floors passing, only for those in the know, that most New York of institutions - The Oyster Bar. The theatrics of the experience make us once again players on the stage of 19th-century ambition. The 150,000 passengers who daily move through the halls of Grand Central - a much smaller building than the original Pennsylvania Station - are players in every performance in the city.

Grand Central is the grandest surviving monument to rail travel, and to the splendor of arrival that it magnified. It's scale reflects a rail network that stretched the length and breadth of the nation. The stations of the subway system, by comparison, are little more than raw structures softened by small panels of decoration. Compare the luxury of the experience in Grand Central with travelling the subway system during those years when an explosion of graffiti inside and outside the carriages made one feel the presence of an invisible enemy. But now the stations are being remade and a programme of art may add momentary pleasure to the journey.

The mediocrity of New York's public facilities stems in part from their formation as competitive commercial ventures and the system is now entrapped in the rival politics of city, state and independent authorities. The crude character of the stations is much less of a problem than the system-wide decline in the structural integrity of tunnels, bridges and elevated railroads. Poorly built from the beginning, in 1904, the infrastructure will shortly need a complete overhaul that will require more money than politics or public budgets can afford. The examples of European public facilities emerge from a tradition of state paternalism; New York prefers to maintain such facilities as joyless necessities and demonstrations of fiscal prudence. Improvements in public transport in Europe enhance the pleasure in public life. In contrast, life on the New York subway has much in common with prison: both are environments that support acts of abuse or violence. Treating people badly makes them behave badly. Designing places that ennoble, as Grand Central does, can transform public life. Some signs of change are appearing: the new station planned in the development at Columbus Circle may be allowed to break through the surface of the street to create a grand concourse. But where is there the ambition of such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, who forced the city to accept the massive railway development that forms the great trench that lies along Park Avenue, its multiple tracks on two decks serving Grand Central Station? Or where (God forbid) is the equivalent of the Robert Moses campaign to mechanise and socialise the city? New York is entering the new century with less ambition and shorter horizons than at any time in its history.

Architecture and the Public Life: Government

In contrast to both architecture of commerce and transportation

buildings for the government, both state and federal appear to suffer

from a lack of confidence and consequent uncertainty over what form

public architecture should take. The new Federal Office building on

Foley Square, designed by Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum and completed in

1997, illustrates the problem. HOK is the nation's largest architectural

practice, with 23 offices worldwide. It is responsive and highly

competent, producing well-made acceptable realities for almost any

programme or culture. Its architects are masters of intelligent

depersonalised realities commodifying uncomplicated uses. By what

process, therefore, does this most responsible of practices create in

the name of the federal government such a cumbersome and authoritarian

object as the building in Foley Square? The public face of the

building, which houses the Internal Revenue Service, the General

Accounting Office and the Environmental Protection Agency in a

multistorey stone monolith, is a parody of the insensitive, overbearing

power of government. The elevation facing the square is symmetrical. The

set-back central panel rises to support a strange oval pavilion enclosed

by a range of freestanding columns. It is clear from a distance that

this seeks to appear as a place of permanence and imperial importance.

Such an image may suit the IRS, but not the EPA. One presumes that federal projects on this scale are the subject of careful critical positioning and much scrutiny. How can it be that such insensitive forms were shaped for such sensitive bodies as the Environmental Protection Agency? The sources are obvious. Such buildings emerged in the 1920s to reflect ambitions and rivalries in the commercial city, their different functions often signalled by the shaping of their rooflines. Buildings carrying temples at their crown sought to give a metaphysical aura to enterprise. The architects of the Foley building should be embarrassed by their casual distortion of architectural signs and symbols. The entrance halls are heavy with columns and the sculptures on the walls deepen anxiety. An eagle softly carved into limestone claws above a bursting sun. It is an enigmatic work that owes some debt to the symbolism of fascism. High above the city, in the rooms enclosed by curving glass, what business of government is being transacted? The same rooms or faithful reproductions of such were used in several movies in the 90's as the power base of demagogues,.

Architecture is not the most substantial or the most disciplined of languages, but in the misuse of symbols, if misuse it is, it trivialises the process of forming an architecture that represents the public realm with distinction. Democracy is a continuous and fragile experiment which requires from architecture inventive explorations of the way the public dimension of a society can be made visible. The aristocratic culture of Europe has given architecture a well-respected role. The rebuilding of the Reichstag to create the European Courts of Justice, new city halls in Spain and new public buildings in France and Switzerland all display the wide-ranging potential for enhancing democracy and the public realm through architecture. In New York, however, as demonstrated by the city's buildings, public agencies do not seek novelty, and architects rarely offer it. The nearby Foley Square Court House building by Kohn Pedersen Fox conveys the same imperialism, but with more charm.

Architecture and the Public Life: Housing

In 2000 the cost of purchasing a home in the city was out of the reach of the majority of the population. Most had to rely on the New York Housing Authority. Over the previous decade the authority began to develop sensitive procedures to restore communities physically and socially Housing and community centres were developed in what had been distressed neighbourhoods, and some of the most thoughtful and unaffected architecture was designed to help restore the many neighborhoods almost abandoned by the development tactics of the 1970's. As an example Agrest & Gandelsonas produced an engaging and complex community-centre building for the Melrose community in the Bronx. Despite the tales of devastation and the obvious dilapidation, in 2000 the Hub on Third Avenue Melrose had become one of the liveliest shopping strips in the city. Throughout this area there were extensive projects rebuilding the streets and neighbourhoods. Melrose Commons led by the architects Larsen Shein Ginsberg + Magnusson is an example of a careful and thoughtful programme of rebuilding with the participation of the community, renewing the texture of the neighborhood by integrating churches and stores in the development. The community clients for the project told the architects, 'Please do not experiment with us'.

Nostalgia

Throughout the 1990's historic

buildings were being restored throughout the five boroughs; Ellis

Island, Brooklyn Borough Hall, and at enormous expense the

infamous Tweed Courthouse (the excessive corruption involved in it's

construction brought down the 'Boss Tweed), but the most satisfying for

the enjoyment of the city was the restoration of so many theaters. New York is a place of multiple performances with music and theatre at its heart. The grid removes depth from the city, and the great walls that line the avenues are composed in an intricate sequence of small theatrical moments, performance halls were restored across New York, some converted to television studios, some reworked to improve performances. Carnegie Hall underwent a decade of restoration and extension under the direction of James Stewart Polshek. And even Lincoln Center home of the Metropolitan Opera House and the New York Philharmonic, and a relatively new complex of building, began an extensive process of master planning and renewal. The demands of restoration led to the formation of expert teams, from acousticians to painters and sculptors and experts on wallpaper and 19th-century carpets. Hardy Holtzman Pfeiffer Associates, HHPA, formed just such a team for the restoration of Radio City Music Hall, which resulted in the remanufacture of all the materials that had dressed the building in 1930. Over the decade of the 90's, HHPA under the direction of Harvey Lichtenstein a much more inventive process of renovation revitalized and extended the several halls that still make up the Brooklyn Academy of Music., including the Majestic Theater the setting for BAM's most extravagant experiments. The interior was stripped of all its applied surfaces leaving a raw shell to carry whatever reality performance demanded.

No grand ideals infected, confused or distorted these restorations. The realities of New York are formed and reformed to remain enduringly tempting to the consumer: every act in the city is essentially an act of consumption. Yet much of this renewal seemed to operate at similar levels of convention and invention, resulting in a busy monotony that lack the surprise or the danger of real temptations. There are dangers aplenty in New York but they're not for consumption. This process of renewal creates a city that is increasingly seen a historical, most of the major streets changed little form the 1920's, and much of the new building lacks the intensity and character of the 20' nothing provokes or promises change (save perhaps the mannered work of some Europeans). This is as much the result of the grid constraining significant change as of the driving force of consumption.

Into the new century within the gaunt shells of 19th-century commercial buildings new stages are being created for buying and selling, offering highly refined theatrics in the elegance and arrogance of new life styles. Distinct from the full restoration of significant monuments this is the renovation of millions of square feet of century-old structures, an area stretching from Sixth Avenue south of 20th Street, across Broadway and West Broadway, south of Houston in acres of massive loft buildings and extending through TriBeCa and SoHo

Signs of restoring and reinventing the past take several forms, from scholarly restorations that, in recent examples, often heighten the quality of the original to renewing the interiors of turn-of-the-century commercial buildings with carefully restored facades by restructuring them to carry the appropriate fashion for any and every kind of use. This is to be seen at its most ambitious on Sixth Avenue, a row of fabulous stores that at the end of the 19th century was called 'The Ladies' Mile', totally forgotten for decades, which somehow saved them from demolition, now renewed and with it the ability to re experience a much grander view of consumption. Look closely at the hundreds of photographs that record the great shopping streets of the 1890s they now can be re-visited with complete familiarity.

The life of a fashionable interior can be short and notions of a progressively changing reality are confused by equal pleasure in all. Past reality is pleasure in retro. There is nothing new in using styles to sell commodities. What has changed is the detachment of styles from notions of identity or signification; a choice of interiors is as likely to offer a stage from science fiction - Comme des Garcons - as a touch of domestic life in the 18th century in the ABC store. Such dissolution of coherent reality is certainly not new. Rome has reformed and reoccupied its ancient structures for 2,000 years. What is new for New York is that the desire to restore has become much as strong as the will to destroy and build again. The culture of the city at the end of the 20th century was one which found it inconceivable that the old Pennsylvania Station could have been torn down and could no longer fathom the political climate in which Robert Moses was able to acquire so much power and cause such disruption.

. These monolithic survivors of 19th-century enterprise may one day become a vast designated landmark district, frozen for ever in the past, removed from the field of speculation. Does the city decline when the spirit to conserve becomes stronger than the desire to develop? (I recall an admiral telling me that he was convinced the decline of the Royal Navy started when the British began to show more interest in sailing ships than in fighting ships.) Imagine the folly of designating huge areas of New York as historic-districts; only the grid was meant to be permanent; limiting the right to speculate would mean the death of the idea.

The city's population is not growing significantly and New York's role as a gateway to immigrants means it is also the gateway to increasing poverty. On a broader scale the northeast of the United States is losing population and there is no evidence that, in the foreseeable future, it will ever again approach the growth rates of the last 100 years. Flat population growth, less and less need for new structures and more need to renew New York's existing infrastructure will lead to increasing support for conservation. A simple listing of the life span of the major elements in the city's infrastructure indicates that the prime activities for architects and engineers in the next century will be the preservation and adaptive reuse of the multiple structures and infrastructures, buildings, bridges, roads, highways, subways, sewers, power plants - on and on - that have grown within the city in the last 200 years. Conflict will arise between the architectural value of the historic structure and the land values that appreciate in a process of continual development. Painful as it may seem, New York is a city made for speculation This conflict between preservation and demolition, between the city made comfortable among the artefacts of the past and a city kept vital by being open to redevelopment, is one that will increasingly complicate the future.

» back to top

» back to top