St Martin's Press - 1995

These essays have been edited from their published versions

CHAPTER 7 - Building Unity ::

Alan Balfour

The city planners, having in general terms dealt with the most critical wounds of the division, moved to what had been for almost fifty years the most doctrinaire of socialist cities, East Berlin. The key sites were Alexanderplatz, the commercial of the prewar working class city, (poignantly evoked in Dr Dublin's novel) then the cities ancient heart and power center, the Spreeinsel and the problem of the loss of the Stadtschloss, the palace of the last Kaiser, on west into the ruined commercial streets around South Friedrichstad

Alexanderplatz

The heart of the former German Democratic Republic, was the eastern gate of the medieval city where the most bitter fighting took place, in the Communes of 1847 and again in the Spartacist uprising in 1918 and 1919 Alfred Dobblin's novel Berlin Alexanderplatz dramatizes the struggle for survival in the mean streets around this place By 1960 it had become the forum of the DDR nation, a place of tangible political and national presence for which there was no equivalent in West Berlin.

The decision to shift the focus of city renewal from the torn edge of the division to the heart of the Socialist city was, manifestly, a political act. It must be said that a fair percentage of the population of East Berlin remain wary of the West and have not lost their commitment to Socialism, and that frequently in the years since the Wall came down Alexanderplatz has been the setting of protests by surviving Socialist institutions against the corruption of Capitalism, these have not lessened over the years. At its western edge the square is contained by the elevated rails of the Alexanderplatz Bahnhof. And behind the station rises the great TV observation tower built by East German engineers to mark the authority of Democratic Socialism over the city, intentionally intruding on the main avenues of the West. The square itself was formed from a Socialist translation of many of the nineteenth-century buildings and activities that had been destroyed by the war. The Tietz department store, the Wertheim's old rival, was rebuilt from the destruction as the Zentrum Kaufhaus, an illusion of a department store that never managed to get over the limited range of consumer goods that were available in the East.

Hotel Berlin City, forty story's high and commanding the square, was built on the site of one of the most popular pre-war hotels, the Grand Hotel Alex. Between hotel and department store had stood the colossal copper figure Berolina, and in the late twenties, a competition to modernize the square led to the construction of the Berolinahaus and the Alexanderhaus, designed by Peter Behrens, both screening the elevated railway and forming a gateway to the square from the West. This was only part of the pre-war plaza to be fully restored. East Berlin architects and planners enclosed the square on the north and east with long walls of buildings that housed the rather uncertain enterprises of Socialism, and paved the whole in a great sweeping spiral, climaxing in fountains and a clock of world time. Uncertain in that they always seemed more an idea than a reality, an idea established around Alexanderplatz with neon lit signs of the major enterprises of government where nothing seemed to change over decades, except through neglect, fading flaking paint, and the dimming of the lights.

The House of the Teachers and the Congress Hall define the southeast corner of the plaza This is the starting point of Karl Marx Allee, initially named the Stalin Allee, which becomes, some distance east of Alexanderplatz, the most conspicuous monument to Socialist planning in the nation. It is formed from long terraces of apart ment buildings decorated with thin classical ornament of slightly oriental effect. The design team was led by Hermann Henselmann, who was also the architect of the House of the Teachers in 1961, a Modernist break with Russia in the year of the Wall's construction. He was the about the same age as Philip Johnson and they knew each other.

Grander perhaps, but in many ways emblematic of the many public places created by East German Socialism, Alexanderplatz was formed over years of struggle to define the appropriate reality for the Socialist future. The peculiar awkward ness of all this work may be the result of either too much theorizing or of the flight of some of the best architects to the West. Embedded in the forms of these rather forlorn structures are layers of complex moralizing over how to create a reality that was anti-history and anti-sentiment. Their non-directed, abstracted communality was intended to represent both a freedom from the enforced civic order which seen as having held the urban proletariat poverty in the nineteenth century; this was coupled with the belief in the transformative power of social modernism. This would either avoid the subjectivity of the architect's personal ity, or the potential inequity of overemphasizing differences between formal types. This architecture would offer a unified transparent reality, a neutral background against which a new society would emerge; a society defined only by the character and achievement of the workers, a rational neutrality free from the corruption of commercialism. The sequence of buildings that stretch east from Alexanderplatz to the end of Karl Marx Allee is an exceptional document of this desire, however misguided, to transform and humanize the city with socialist virtue.

The Berlin Senate's decision to redevelop Alexander platz as a commercial and corporate center of the city must have been initiated, to some degree to erode the reality of socialism. However, the decision to move the German Parliament from Bonn to the Spreebogen made it symbolically inappropriate to allow high-rise speculative corporate buildings to overshadow the Reichstag and the renewed political center of the nation, thus the move to 'Alex'.

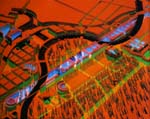

Given that this competition was explicitly con cerned with establishing a general framework for commercial development, most of the submissions seemed unable to define the city in terms other than architectural form and character. The most extreme example of this again came from Daniel Libeskind as he continued to evolve his highly subjective view of public order. Several years of demanding involvement with Berlin's bureaucracy had made him keenly aware of the emerging political struggle for Berlin's future. A struggle he would posit between regression and progress. He wrote:

Intrinsically mysterious, It develops more like a dream than a piece of equipment. I have challenged the whole notion of the master plan with its implied totalism and finality. .rather, I have suggested the open and ever-changeable matrix which reinforces the processes of transformation and sees the dynamic of change in a diverse and pluralistic architecture. .. [treating] the city as an evolving poetic and unpredictable event

That's what he wrote but what he proposed was totally lacking in any semblance of an 'open and ever changing matrix,' instead he offered an obsessively detailed description of a city center in which every object would have had to have been controlled by him. It was a proposal without general principles, nothing to suggest a means of achieving a 'diverse and pluralistic reality.'

Though he claimed to be searching for a resilient fabric in which to form a future inclusive of the past, in opposition to those who would form the future in eighteenth-century notions of order, all he offered was peculiar reality of his making. The political symbolism of this debate is less revealing than the disturbing limits it reveals in the ability of architects to conceptualize and project the future of the city.

Alexanderplatz, brought the restless even disturbed orders of Libeskind into direct competition with the bleak certainties of Hans Kolhoff. They were given first and second places, after passionate debate the conservative Kolhoff was the victor.

Kollhoff's master plan appears to be based on, of all things, a close reading of Raymond Hood's plan for New York in the late twenties. This established a mass grid of twelve-story city blocks as the base for a higher order of towers. In Hood's mind, the authentic commercial city was a direct expression of market forces, highest use reflect ing highest value. In Kollhoff's Alexanderplatz, the highest use will take place on a short, uniform stretch north of the plaza: Berlin's equivalent of 57th Street by the Park, will be defined by the checker board placement of six or seven high-rise buildings that just avoid overshadowing each other. Again Hood's imagi nation seems to underlie the form of the high-rise structures. The sections narrow to allow for natural light and air, and the varied setbacks echo Hood's pleasure in expressing the reduction in the elevator core as it moved up through the building. Both here and in his submission for Potsdamerplatz, Kollhoff appears to be fasci nated with Rockefeller Center and the great east-facing wall of the RCA building, where setbacks lovingly express the internal dynamic of the building and give a sense of sublime ascendancy. (The American city is so much the product of commercial speculation that it is little influenced by European vision.) Kolhoff proposes a unified character to the architecture area, constraining the tendency to excessive individualism so disliked by the Berlin authori ties, unless it comes from him. It is unclear whether the city will attempt to impose controls to achieve such a unified architectural effect or whether it will bend to the demands of the developers. If the latter, Hood's model has strength enough to be formed into a set of codes and principles that will accommodate the individual needs of developers and architects. But it is strange that this potent technological culture, and potential capital of Europe, should construct its future in the shape of New York in the Thirties.'

Spreeinsel

The sequence of competitions which began in the vision of a new Berlin as the capital of the United States of Europe ended in Spreeinsel with the appearance of a retreat from the future. The Spreeinsel is the area of he city re-planned by Schinkel in the early nineteenth century, to become one of the most gracious public squares in Europe. The ostensible task of the lnternational Competition for Design Ideas, was to accommodate the many institutions of government that would be transferred from Bonn but it also had to face the much more value laden problem what to do with the stretch of land that had been for five hundred and more years the heart of Prussian aristocratic power, particularly what to do about the DDR Palast der Republik which partly covered the site of demolished Stadtschloss, the last home of the Kaiser. (It is the stretch of land at the center of the engraving from 1650 in the prologue.) The dream of restoring the Stadtschloss had never completely disappeared not had the sense that such a restoration would recover more than a building.

The Stadtschloss (or the Konigliches Schloss) was founded by Elector Frederick II in 1443, and rebuilt in 1698 under the direction of the architect Andreas Schluter, by the first king of Prussia, Frederick I, With the great west front designed by the Swedish architect Eosander von Goethe In the nineteenth century the palace was altered and enlarged by many architects, including Schinkel, and by the end of the century had become the Berlin home of the Kaiser Wilhelm and it was from the Stadtschloss that he directed the First World War in to disaster. The Second World War reduced it to a shell and the Communists demolished it as a symbol of imperial oppression The center of the west facade, however, had a particular importance in Communist history as the place where Karl Liebknecht had proclaimed the creation of the Socialist Republic on 9 November 1918, so it was rebuilt into the DDR building, adjacent to the palace site.

Over a thousand architects from across the world entered, the majority projecting there own fantasies for the future onto a city they barely knew. In 1992, the publication on the Spreebogen competition reproduced every entry, revealing a great diversity among the finalists and a critical interest in the conflict of ideas. A parallel document produced by the same publishers for the 1994 Spreeinsel compe tition chose only to represent fifty-seven out of more than one thousand entries. And with few excep tions these were the entries offering a conservative vision for the future. Over a period of two years, confidence in a radical architecture has noticeably waned. The results brought Berlin's dreams down to earth.

In his critical commentary on the results Dieter Hoffmann-Axthelm wrote:

There are only two reactions to the giant competition with its meager yield The first quite obvious is to shrug and say money changed hands, and that was it The second reaction, in view of the disproportion between procedure and results, would be to enquire into the reasons that led to this disproportion, and look into the reality beyond the competition proper. Its most important result was determined before it began to restore the city's historical layout.

In future, effort will be required to recall that this indeed was the point of departure The actual result, in contrast, proved no more than what might have been obvious to thinking people from the start that filling the gap with modern architecture, without previously finding a social consensus on how this is to be done, cannot work. This is certainly worth reflecting on. and if the competition, which is said to have cost over four million marks, has demonstrated its own limitations to the general public and government users, this is no mean achievement.

The winning submission from Bernd Niebuhr proposed returning the ancient heart of the city to the scale and character of its late-medieval past, that the mass of the Stadtschloss reestablished, and by implication the DDR Palast der Republic be demolished:

The Palast der Republik, the Peoples Palace of the former German Democratic Republic is serious yet awkward modernist pile, but was still loved by many unreformed socialists in the city. Its major offence was not the quality of the architecture but in having been consciously built over the foundation of the Stadtschloss Built atop the Stadtschloss as a deliberate symbol of the triumph of socialism over aristocracy and autocracy, and as a lasting monument to the anti-fascist and democratic gains of the GDR. Those seeking to replace it argued that rebuilding the Stadtschloss was essential to resurrecting the ancient heart and spirit of the city.

Sud Friedrichstadt

South Friedrichstadt, immediately east of Leipziger- and Potsdamerplatz was the brightest commercial district in prewar Berlin. It languished in a semi ruinous state throughout the socialist years and was after '89 setting became the focus of extensive redevelopment and restoration. In the pre-war years Friedrichstrasse was the great commercial street of South Friedrichstadt. Its 17th and 18th century grid of streets were to establish the subsequent form of the city. At the end of the century much of the area still showed the ravages of war and the task for redevelopment was mainly one of filling in the checkerboard of gaps that had remained abandoned for more than fifty years. Appropriately all new development has constrained by the historical form of the district and the issues of critical interest are the varia tions in reconciling the developers' need for distinct identity with the city's interest in sup pressing individual character in favor of the civic whole.)

Surprisingly the most significant building project from the last year of the Communist regime took place in the district on Oranienburgerstrasse, the restoration of the New Synagogue. No other building embodies more completely the tragic and disturbed history of these streets. The largest synagogue in Berlin, it was called New to distinguish it from the Great Synagogue founded in 1714. Among the three thousand present at the official dedication on 5 August 1866, were major figures from Berlin's political and cultural life including Reich Chancellor Bismarck. The architect was Eduard Knoblauch and the interiors were by August Stuler, both were Christian. For some it was a glorious presence, for others its Moorish character and great golden dome were problem atic. Writing at the end of the 19th century social critic Paul de Lagarde asked:

What does it mean to claim a right to the honorable title of a German, while building your most holy sites in the Moorish style, so that no one can forget you are a Semite, an Asian, an alien?

Within the Jewish community a Hamburg rabbi, Max Grunwald, wrote of his concern that the Christian architects for the synagogue had over-emphasized the 'Oriental' in Judaism. 'They have,' he wrote, 'unintentionally earned the thanks of the enemies of the Jews.'

The New Synagogue became the center of Jewish culture in the city. As the persecution of Jews and Jewish interests became explicit and began to expand, the Synagogue gave spiritual comfort and hope to the community. It initiated a series of concerts and oratory performances to which all of Berlin were invited. In 1935 it was the setting for the premier of the oratorio by Ferdinand Hiller, The Destruction of Jerusalem. The last performance in the series, Handel's Saul, was held early in 1938. On Kristallnacht (9-10 November 1938) the attackers were confronted by the chief of the district police and damage was minimal. The celebration of Rosh Hashana in September 1939, was the last ceremony conducted in the Synagogue and while the service was in progress the city authorities covered the golden dome with gray paint to protect it, as they explained, against air raids. Into the war it became an air raid shelter and clothing store and there is evidence that the Reich genealogy office used the basement to store records until it was gutted in the bombing of 1943. After the war it sat abandoned behind wire fences, a desolate hulk with no community to defend it. The great hall was demolished in 1958 for what the East Berlin authorities claimed were safety reasons. There was an attempt at restoration in the years leading up to the Synagogue's hundredth anniversary in 1966, but to no avail. Eventually on the fiftieth anniver sary of Kristallnacht the GDR pledged itself to the Synagogue's restoration, and the symbolic corner stone was laid by- Erich Honecker on 9 November 1988. The work drew on the many East German organizations specializing in historic restoration, it must be recognized that for all its Stalinist orthodoxy many distinguished aspects of German cultural life survived and flourished in DDR. And once again the golden and faŤade is a brilliant presence on Oranienburgerstrasse, for so many years was one of the saddest streets of the city. However only the reception halls remain, the great hall may be reconstructed in the future, but for the present architect Bernard Leisering has outlined its form in glass surrounding few surviving fragments of the destruction.

Moving west from the Synagogue to where Friedrichstrasse meets Oranienburgerstrasse was a typical example of the condition. The surviving shells of buildings were occupied by a loud highly extroverted group squatters after the Wall came down. They made court back from the street the setting fro many apocalyptic musical and theatrical performances. In redevelopment the architect Josef Paul Kleihues filled the whole block incorpo rated the surviving structures along the street and traversed the interior with two long arching atria, one of which connected to the remains of the grand portal to the Franz Ahrens department store of 1907

Down the street at Unter den Linden there developed several thoughtful examples of the new civic order. Christoph Mackler offered a powerful urban palace on the Lindencorso set on massive battered piers, and further along architect Jurgen Sawade displayed a much refinement in the layered complexity of the facade of Haus Pietzsch. The leaders of this conservative group; Kleihues, Hans Kollhoff, Max Dudler and Jurgen Sawade, can be seen together in the repair of the block south of Unter den Linden, between Franzosischestrasse and Behrenstrasse. The result shows interesting differences in personality but overall, as they intend, the mass of the block is stronger than the character of the individual pieces; all very reserved and German and somewhat ominous.

This is in distinct contrast to the most considered area of redevelopment along Friedrichstrasse immediately west of the Gendarmenmarkt and Schinkel's Schauspielhaus, the Friedrichstadt Passages. After a competition between twenty or so developers, One city block, the Galeries Lafayette department store was awarded to Jean Nouvel. In the constrained field of the commercial city this fragment of French desire remains a burst of Gallic optimism. Nouvel created a sparkling transparent pavilion, its facade playing between a surface of illusions and the reality within. Large screen images over the entrance lead to a conical atrium that runs the full height of the building and whose walls carry continually shifting distorted projections. Although the results are less forceful than the drawings, the completed work conveys sheer pleasure in the emergence of new realities and the promise of new technologies.

The other chosen architects, Oswald Mathias Ungers and Henry Cobb of Pei, Cobb, Freed and Partners were asked to prepare theoretical models considering the how to formally interrela te the three city blocks. Ungers strongly criticized the intent of the initial planning study which examined the creation of an interior passage back from Friedrichstrasse. With his submission he wrote:

Any change in the historical block structure would represent unjustified interference in the traditional cityscape, and result in the destruc tion of an eminently important urban structure. Neither the Marxist urban development experiments of Hilberseimer, nor Scharoun's landscape ideology with its impact of urban destruction, nor the Smithsons' movement patterns, nor the bombing raids, nor even Socialist planning, were able to alter the historic pattern of Friedrichstadt.

Ungers viewed his architectural role as servant to reason and history. He created a massive block from narrow sectioned walls enclosing courtyards, which were to naturally lit and ventilated unlike the air-conditioned artificiality of Nouvel's scheme. The bulk of his building exceeded the historic height limits and so was given a civic facade suitably dressed in stone. His self-righteous commitment to conserving the 'historic pattern of Friedrichstadt' by forming it with such willful ordinariness is contradicted by the evidence. The Friedrichstrasse of the 1900s exists in hundreds of photographs showing a riot of enterprise, each store and office an entertainment vying for attention; architecture speaking in all the fashionable tongues. Texts cover all the buildings, from the Friedrichstrasse Panoptikon to the Victoria Cafe, in a vulgar but exciting display of competition and enterprise. By this measure Jean Nouvel's Galleries Lafayette is the most faithful of the new schemes to the history at the place.

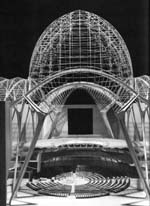

The third project emerged from a study by Henry Cobb, (from the former partnership of Pei, Cobb, Freed, with many years of international influence.) He proposed re-forming the city block with monoliths constructed of bands of glass and stone, battered and sculpted to emphasize their mass. Through this he would have made two cuts, one orthogonal, the other arcing, creating in the space between sequences of gallerias under similar great arches. Despite the objections from Ungers, who believed that it would weaken his proposal, a powerful affect that could have been given by taking the street into the building. Unfortunately the Cobb project as built, lost much of this strength the street architecture becoming confused and over-elaborate.

Checkpoint Charlie

On to Checkpoint Charlie the most dramatic point of entry through the Wall from the West. This was the gateway to the Socialist empire crossing this line one entered in a communist world that stretched from Berlin to the Pacific. The memory of this once dramatic stage now lies beneath the Checkpoint Charlie, Friedrichstrasse Business Center. It is also known in Berlin as the ABA, the American Business Center. This formed from a series of elegant, uncomplicated commercial structures, progres sive and pragmatic in contrast to the projects of the two American architects within the complex, Philip Johnson and David ChiIds of SOM. Johnson has raged in print about the controls which he believes make the production of architecture impossible at this time in Berlin. His work here either reflects his anger or the incompetency of old age, a wall of mildly decorated buildings without specific character. (The developers however were pleased to advertise the presence of this world famous architect and for a while the project was promoted with his portrait on a large billboard in the center of Check point Charlie, until it was stolen . The asked for help in solving this theft and were send Johnson's ear carefully cut from the picture.)

Much more confidant is the work of David Childs; (leader of the New York office of Skidmore Owings and Merrill, SOM,) though almost too active for its neighbors, it is shaped from metal and glass, into a lively assertion of the ability of architecture to both represent and support complex weavings of events and structures. It is left to ChiIds to memorialize the crossing at Checkpoint Charlie with the symbol of a raised gate, strapped prow-like to the facade of the building. (SOM from their several offices continue to create works that shape the character of world cites and are having a dominant influence on both New York and Shanghai.)

East of the American Business Center, the block framed by Zimmer- and Charlottenstrasse has been completely rebuilt by Aldo Rossi. It is revealing to compare this with his architecture for IBA in South Friedrichstadt and South Tiergarten. The early work is disturbed by its awkward mass and elemental formalism, the great single column holding the corner on the Kochstrasse a symbol of communalism. On Zimmerstrasse, however, Rossi presents a pastiche of the block's former self, a confected series of linked facades changing character in response to the historic lot lines. Drawn from four or five variations in color and proportion these facades convey the impression of a city formed from an association of different uses and enterprises, however these are merely cosmetic facades on a wholly standardized commercial interior across the whole block. In the earlier work from 1984, there was a poetic need to recognize the disturbed memories of the place, yet this even sadder place having lain ruined in the shadow of the Wall for thirty years is only effect no poetry.

For decades, on the block adjoining the Rossi work stood the barely recognizable face less hulk of Erich Mendelsohn's sweeping addition to the Rudolf Mosse publishing house in 1922. What had been an addition to a nineteenth-century structure damaged in the Spartacist Revolt of 1917 is now a recreation of a 1920s structure added to a 1994 office building. The reproduction of the Mendelsohn building is so clumsy as to damage his reputation.

Way beyond the center means are being considered to use architecture to unsettle the culture of the city built by Socialism. The first major experiment is in the largest of the public housing estates of the former East Berlin, far from the great historic districts of the city. Marzahn, what one city official called, the 'Oriental labyrinth of Marzahn.' remains the largest high-rise public project in the Socialist city, housing some 200,000 people in long-walled apartment buildings divided by parks and landscapes. Even in the turmoil following the reunification the area has always seemed well maintained without signs of social decay. What then was the reason for the city's interference - if not to disturb and covertly undermine the Socialist content of the place and the architecture? From the mid-nineteenth century Berlin's urban poor had been increasingly imprisoned in the dense tissue of its tenement structures. The Socialist state set out to invert this condition. To free the workers it wholly re-made the city, placing housing in informal parklands surrounded by light and air. Marzahn was the most extensive construction of this new reality, and many of its residents felt a sense of defeat in the re-unification and resented the crudeness of capitalism. However for all but the most discerning eye the differences between the post war public housing in East and West Berlin are imperceptible. Walking through Marzahn in the summer of 2003 the impression was that little had changed since the Wall, save the Trabants had been replaced by the smallest Volkswagens.

The thousand of drawings that were created to re-imagine Berlin can be seen as a collection of failed desires for the united city. Some of the results have produced a simulacrum; places that are more illusion than authentic. Many streets and neighborhoods in both the former East and West, have regained a brooding intensity and even sexual, but this is more by commercial exploitation that by tasteful planning. Yet in vast sectors of the city the social realities and physical conditions present when the wall came down have remained largely unchanged. Berlin had much less need for the dreams of idealists that some hoped for. This apparent conservatism in recent years has as much to do with shifts in world ambition as it has with Berlin. The growth and the change in a city is subject much more to market forces than to the dreams of architects, and cities naturally define their character in the consensus of broadly accepted forms. The question for Berlin -the question to be asked of the urban decisions already made is whether the attempt to constrain the configu ration of the future city will equally constrain Berlin as a financial center; will act to weaken its world role when in competition with cities more tolerant of speculation such as Tokyo, New York and Shanghai.

Using the city as an explicit instrument of national ambition is inevitable; it is the form chosen that can be questioned. Tapping the world's imagination led to no ways of expression and enhancing civic life. Nor is there any concern to provide the archaic spatial matrix of this new Berlin with any tolerance for the impact of new technologies of transplantation and energy use or the changes of social reformation This emerging Berlin has no trust or pleasure in the scientific promise of the third millennium. This Berlin will socialize its population on a nineteenth-century civic stage, and there is no telling how it will respond to the myriad desires that this arrangement will suppress.

How do the sum of the projects that have rebuilt the city measure against the stark oppositions that divided prewar Berlin, between the intolerant conservatism of the Nazi's and the untested dreams of the Moderns. For the most part the order of the streets and buildings of the new city is small scale easily compromised sometimes regular sometimes not, nothing dominates, except in the highly ordered walls of the Bundestag compound, a dominant order that creates, not only a stable frame for government but a bridge across the line of division. Time and progress are seen and defined by changes in fashion with any expectations for changing society. Awkward and for some painful memories persist in the socialist housing estates around the Eastern city, and their unreformed socialist populations. Populations who remain firmly opposed to the attempts to destroy the communist parliament and rebuild the palace of the Kaisers. Otherwise the past is mildly recognized and at best sanitized. The symbolic power of architecture is nowhere more evident that in the ability of one architect's vision to restore the Reichstag as a glorious and powerful presence in the popular national and world imagination. Elsewhere the varied shape of the future, in the architecture and institutions, public and private, are an uncommitted mix of the contextual the informal and there is nothing in the confusion but confusion. Just as progress has become a fashionable illustration, culture is mostly defined by consumer goods and popular entertainment. And the producers of such consumer goods increasingly co-opt Berlin and other world cities as the props and frames for their media campaigns. So while architecture may have become a minor and overly personal from of media activity, it is media in many forms that is giving the city new significance.

Predicting the desired future from the evidence of planning and architecture is slightly more reliable than reading tea leaves in a cup. The absolutist imperialism of Hitler's vision translated into a city of a vast and controlled order dominated and emanating from the Great Hall. Scharoun's city would have been it antithesis, but equally dictatorial in its cultivated disorder. The new can be seen as a series of local optimizations, but the new power center, the new Stadtschloss is not the Reichstag but the cluster of world corporations around Potsdamerplatz. All architecture is a project into the unknown. It is impossible to say whether opportunity has been lost and whether the future of Berlin would have been profoundly different if the more transformative and radical projects had been chosen. What has emerged from the evidence of what has and what will be built is the clear realization that, since the Wall came down, Berlin has slowly retreated not only from any attempt to idealize the reality of the future. From the evidence of history that is probably good.

» back to top

» back to top