St Martin's Press - 1995

These essays have been edited from their published versions

CHAPTER 7 - Building Unity ::

Alan Balfour

The Wall collapses:

The events leading up to the collapse of the socialist regime began on October 8, 1989, during the celebration of East Germany's fortieth anniversary. The ceremonies were attended by Mikhail Gorbachev, whose presence became the catalyst for protestors. What began with small crowds of demonstrators chanting “Gorby! Gorby!” and “Freedom! Freedom!” led by nightfall to clashes with police involving several thousand demonstrators, the depth of the popular dissatisfaction with the East-German government became dramatically evident. The Communist Party, support for liberalization appeared from the beginning to have had the tacit support of Gorbachev.

On November 9, East Germany lifted restrictions on travel to the West. Within hours, tens of thousands of Berliners from the East and the West swarmed across the many miles and layers of the Berlin Wall, concentrating on the long-closed entrances to the old city at the Brandenburg Gate and at Potsdamer Platz. Drinking and singing and kissing and hugging, they remained throughout the days and nights that followed, unwilling to leave this scene of epic transformation. They came armed with hammers and picks and axes erasing the Wall, chip by chip. “This is what we have dreamed of since we were tiny children,” said a twenty-three year old East Berliner, moments after he crossed into West Berlin at Checkpoint Charlie. He said call me Knobi. “We heard the news at 11:30 PM, then when we heard they were letting people through, well here we are.”

Immediately people began to image the reality of unification, and as the passions settled three major projects emerged as central to the reconstruction; first: creating master plan for Potsdamerplatz and Leipzigerplatz which had been the heart of the commercial city before the war and had in the division become the most a most poignant lost reality trapped between the two lines of the Wall. Second, with the momentous decision to move parliament back to Berlin was the need to master plan for al the institutions of the Bundestag, and third at the heart of the Bundestag to rebuild the Reichstag s a fitting symbol for a unified Germany.

Potsdamerplatz

Within months of the removal of the Wall, all kinds of visions were projected onto this place, most far removed from architecture. Even before the task became official, a strange selection of international architects was invited by the Frankfurt newspaper, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), to dream of structures to fill the void between East and West at Potsdamerplatz. American Robert Venturi offered a giant skeletal stair that would rise and fall on either side of the Brandenburg Gate. Grassi, in very careful drawings would offer a solemn and massive architecture to define the post-Wall city, which turned out to be surprisingly prescient. Bernard Tschumi, lacerated the edge of the Wilhelmine city into a succession of tendon-like bridges across the divide. The most vivid image, however, came from the loose pen of Aldo Rossi who created a careless starburst of energy around the pro jected figure of the octagon. The spontaneity of the drawing did much to disguise the essential conservatism of the architecture.

Until the Wall collapsed the official maps of West Berlin described East Berlin exactly as it was in 1939, with all the pre war buildings and property lines clearly demarcated. The most immediate res ponse to the demise of Socialism was a blizzard of lawsuits reclaiming land lost in the division, reclaiming the past.

And just as the architects were beginning to image a new city, international developers were imagining the vast profits to be made from the development of a free Berlin into a world financial and corporate center, and Potsdamerplatz was viewed as the most opportune field for speculation. Corporations and developers struggled to acquire possession of the extensive areas of land between the Kulturforum and Leipzigerstrasse. In association, they employed Richard Rogers to produce a master plan for the area. This emerged with streets radiating out from a cluster of towers, all in steel and white, around Potsdamerplatz. (Around the same time Rodgers was asked to conceive of a master plan for the new district of Pudong in Shanghai, similar scale and similar vision, increasing one sees the emergence of few imaginations that appeal to world desire.) By the end of 1991 the battle for land acquisition was over. The northwest sector went to Sony, the south east sector to the Asea Brown Boveri Corporation, and the largest, the southwest, to the Debis Development Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Daimler Benz.

In reaction to the aggressive corporate invasion the City scrambled to regain authority and launched a two stage competition to establish in broad terms a master plan that would not only heal the 'wound', but would resolve the discontinuity of realities that the years of division had produced. Pre-war, this whole area had been formed from a continuous mass of building defined by the grid, the street plan and the roofline. The post-Wall condition was presented with the sad remnants of the nineteenth-century city on the East with the intentional mis-order' of Scharoun's Kultur Forum on the West, the grimly decaying blocks of a lost bourgeois city, meets the unfulfilled promise of existential revolution By what order could such opposing realities be conjoined?

The historical street pattern was to be reinstated wherever possible, and the competition required the accommodation of the few buildings that survived destruction -most notably the Espla nade Hotel.. The octagon of Leipzigerplatz was to be restored and a grand pub1ic promenade was to be created to the southwest of the tracks that had formerly carried the trains to Potsdamer Station. The first stage would select a spatial master plan and the second stage would develop the architectural.

The Master Plan

The many entries submitted in the summer of 1991 projected widely differing visions for the city and widely differing forms and order to the city plan. Few entries a had a character and a power equal to the task. Oswald Mathias Ungers (placed second) proposed forming new urban structures in the intersection of three distinct spatial orders -the plans of the historic streets were to be overlaid with a dense grid which would re-define the order of the mass of the city, giving rise to a widely spaced series of towers ordered by diagonal overlay on the base. A theoretical proposition it developed charac ter from the chance relationship between each condition. It showed little concern for the realities of real estate development or the great diversity of use that the strategy would have to support. It seems to seek to make explicit conflict bet ween civic order and corporate speculation.

The fifth place went to Axel Schultes 'At the Potsdamerplatz junction, 'he wrote 'everything is different a construction has become a place. A confrontation beyond compare, a collection of the third, of the fourth kind is trying to find spatial image here.' His solution-'to release seam and gulf, break and continuum, density and ease of interchange, construction and space, sharp and blunt edges, sieve and pot'-is to unite the two plazas around a major subway station on Potsdamerplatz, with Leipzigerplatz becoming its covered forecourt. He perceptively uses new performance to change the play of the city. Later he was able to affect a more significant part of the city.

Tow schemes represented the extremes of desire that Berlin held for the international imagination in 1991, Hans Kollhoff and Daniel Libeskind; they offered polar opposites. Their differences are as much in the intangible qualities of character and intention. Kollhoff re-centered the city around an absurd gathering of pseudo-American skyscrapers encircling Potsdamerplatz, an ersatz Wall Street in variations on the theme of the Rockefeller Center- the image of enterprise without the uncertainty of speculation. While Libeskind find in exercise the opportunity to take his imagining to the city, and to a construction that would seek atonement for all the conflict of the century and:

Always talking Libeskind stated that:

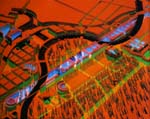

'the identity of Berlin cannot be reformed in the ruins of history or in the illusory reconstruction of an arbitrarily selected past.' The new city must be allowed to emerge out of a mosaic and a puzzle, the site to be intersected 'by ten thunderbolts of absolute absence.' (?)

The resulting site puzzle would allow entry into 'the post-contemporary city where the view is cleared beyond the construction of domination, power and the grid-locked mind.'

The mosaic was to be formed from fragments of other European cities, the fabric to carry a dense matrix of all the events and programs of the city, a heterogeneous policy the only goal. The only priority would be that 'a small child should discover a dream and an imaginative future'. Dominating all would be the 'Resonating Plate' a great inclining plane flowing over the most stressed center of the wounded city. Potsdamerplatz. Owned by all people, with soil from the world on the roof, the wilderness of Berlin on the ground and in the ploughed other earth/reality much would happen…the possibility of cultivation, streams of seeds, powered by wind and sail, the eye-l-cure, thunderstorms, skyhooks, artificial sun/rain, spark-writing, plantation in the clouds, the water fall, inspiration all necessities in the Berlin of tomorrow.

Alas the 'Resonating Plate' as drawn seemed powerless power of the idea, and this egocentric vision, remains a passionate demonstration of the obsessions of an individual will.

The jury award first place to the Munich architects Hilmer and Sattler. Throughout the architectural and planning world and particularly in Berlin, there was disappointment. It confirmed for many that there remained a deep conservatism in the institutions controlling the newly united city. The plan was the least ambitious and the least romantic of the many hundreds of dreams projected through competition onto the city in years immediately after the Wall came down. It suggested the influence of Rob Krier with his lyricism. At a time when many believed that Berlin could become the exemplary city of the new millennium, the Hilmer and Sattler plan was a consciously modest proposal, free from Utopian desire, free from the promise of reformation. In every element it presented a future formed through an unassertive reassertion of historical order.

Final solution

The Hilmer and Sattler plan defined a spatial envelope which would contain all future development across the area. But it came too late to constrain the Sony Corporation. Future generations may wonder how a Japanese corporation gained the privilege of building higher and with more originality than anything else in the area. The answer, they were swifter and stronger than the competition. Their corporate headquarters, with its great atrium and tower, is the only record of the ambitions for dreams for Potsdamerplatz before they faded beneath the dead hand of the master plan.

The development of Potsdamerplatz continued with a second-stage competition to choose the architect to design the southeast sector - consistent of course with the new master plan. There were many proposals, but such were the constraints of the master plan that the resulting entries were almost indistinguishable one from another. Isozaki's submission was typical, it showed a gifted architect's struggle to derive character from a highly constrained context. Kollhoff's revised submission strips away all reference to the American skyscraper, with an architecture devoid of any subjective inflection. The drawings have an ominous character, they offer neither the shock of the new nor the ghost of the past, only an denial of the present. Success went to the Genoese architect Renzo Piano. What distinguished his work was the way it articulated the relationship between the new Potsdamerplatz and the awkward edges of Kulturforum.

In a symmetrical conclusion to the first visions for the uniting of the city, the architect selected from a limited competition to build the south-west sector was Giorgio Grassi, whose project not only obeyed the master plan but also echoed the same rationalist come fascist order that he displayed when responding to FAZ on the fall of the Wall.

New Potsdamerplatz was planned in four sections by four major developers, all within the constraints of the Hilmer and Sattler master plan except the headquarters of the Sony Corporation in the northwest sector, whose German American architect Helmut Jahn completed the design before the master plan was enforced. The Debis development corporation of Daimler Benz, in the south-west sector was under the overall direction of Genoese architect Renzo Piano While in the south-east sector, the investors ANT and ABB selected the Milanese architect Giorgio Grassi's designs. The northeast sector came much later, developed for department store corporation Hertie Kafstadt AG in 1997.

What began as a speculators' free-for-all was brought under close regulation, first by Hilmer and Sattler's master plan, and second by the greatly increased influence of the Senate De partment for Building in the structuring of com petitions and the selection of architects. The greater the control, the more explicit the con servative vision for the city became. Although all the principal architects in the various sectors were foreign -and there was no evidence of a retreat from using non-German imaginations -the master plan from German architects. Hilmer and Sattler's plan would establish a specifically 'Berlin' character for the new city; a character that reasserted the eighteenth century form of Sud Freidrichstadt to establish the twenty-first century order.

In it's development the master plan separated in to three quite distinct sectors, and three quite different owners- Sony to the north, Daimler Benz with the largest plot to the west and ABB on the east. There is a fourth sector Leipziger Platz, perhaps the most emotive of all and where the memory of what is still very clear, and simple enough to be recovered. But sadly it's reconstruction is the most piecemeal and compromised by the claims and ambitions of the surviving prewar owners.

Sony Corporation

Eighteenth-century order for all save the Sony Corporation. Though not exceptional in relation to commercial develop ment in other financial capitals, the Murphy/Jahn complex of buildings gave the city a far more ambitious, and resilient architectural performance than anything else in the new Potsdamerplatz. This is Helmut Jahn's most satisfying work in recent years, relatively free from fashionable mannerism, the whole is enclosed by walls that both hold the street line and open, invitingly, into a soaring atrium, where the illusions created by Sony technology are presented with great theatricality, under what a great tent. It easily incorporates the remains of the Esplanade Hotel. It is a triumph of corporate culture consuming the public realm. Sony chose Jahn directly without competition, the other sites were the subject of international competition.

Daimler Benz

In the southwest, the largest sector, the strength of Renzo Piano's response to the Hilmer and Sattler master plan lay in the way he married the new development with the awkward eastern edge of Kultur Forum and won him the competition. His plan re-established the tree-lined avenue of Potsdamerstrasse to lead to a public plaza surrounded by hotels and theatres created out of an extension of the Scharoun library on the west and the Daimler Benz pavilion on the east. The unsettled edges north and south became an extensive landscaped water garden. Piano invited many colleagues to participate in creating the architecture, including. Rafael Moneo, Oswald Mathias Ungers, Hans Kollhoff, Richard Rogers and Arata Isozaki. Each in his own way establishes the identity of this central part of the new city within the constraints of the master plan and the instructions of the developers. Whereas the Sony headquarters seduces one into the consumption of a grand illusion of the public realm, Daimler Benz contrived a more authentic civic life with much less affect. The project as built consisted of nineteen buildings, including three medium rise towers, with a total of 1.8 million square feet of space. More than half is used for offices, 20 per cent for apartments and the rest for a mix of restaurants, musical and variety theatres, a conference center and a casino. At the heart is a 200-metre-long shopping passage under a retractable roof. It has become home for more than 7,500 people and more than 100,000 work here every day. Yet for all its good intentions and careful stage management this after 5 years of use is a simulacra of city life in which the corporate ordering of experience dominated and the 200 meter long shopping passage, which sucks all the life from the new and pleasant and empty streets that surround it.

A+T (Asea Brown Bovari with Terreno)

At the other extreme the Giorgio Grassi development for A+T produced an overly respectful response to the Hilmer and Sattler master plan. This has resulted in a bleak, uninflected sequence of twelve-story building blocks, denying the street and chilling the experience of public place. It ends at its northern limit with a massive curving building, which consciously follows the footprint of the great pre-war entertainment center which stood on the site, Kempinski's Haus Vaterland. Apart from this modest reference to history, elsewhere a uniform facade runs across all buildings, satisfying all uses, formed from an identical repetition of gridded walls and small windows. Its ruthless elimination of gratuitous meaning has made it the subject of harsh criticism. Grassi's considered use of particular architectural and planning qualities is in marked contrast to the poetic power of Christoph Langhof's vivid proposal for the Pressehaus on the adjoining corner east of Grassi's project. Architecture can give as well as take. It is also interesting that for all the ascetic conviction of Grassi's architecture, it does not obey the most signifi cant element of the Hilmer and Sattler plan, that of maintaining a wall of buildings along the street facade. Grassi instead withdraws the mass of his buildings from the street, forming courts in which the presence of civic order becomes both remote and at the same time intrusive.

The memory of Haus Vaterland only serves to exaggerate the change in both the pleasures of architecture and the performance of city life that have occurred since 1920. Remember it was known as Haus Piccadilly when it opened in 1913, and Haus Potsdamer during the war, and renamed Kempinski's Haus Vaterland in the 1920s after the wildly successful Berlin restaura teur, Hans Kempinksi, who converted a dull parade of Wilhelmine dining halls into a confu sion of bars and cafes each offering dramatically different theatrical realities. The most sought after of all, a table on the Rheinterrasse high above a miniature valley of the Rhine where every hour, on the hour, a furious storm descended from the hills with manufactured wind and rain pounding the windows. This mere fragment of unreal desires from the twenties city is much closer to Sony's world than to Grassi's Berlin.

A comparison of these three sections of Potsdamerplatz reveals three distinct realities, at three different speeds. Jahn offers the confected optimism of the commercial world. No great interest in the street, all the impact and power is held within the atrium, enhanced by the illusions of realities created by Sony technology in which the citizen is manipulated passively into consumption. This is a high-speed, sensational, ephemeral place, selfish and progressive, and deeply tempting.

Piano has re-made the southwest sector in the image of the new Euro pean city, with self-conscious construction of new streets, urban blocks and public squares. Yet this is also a corporate construction, with only the illusion of civic life, in which variety comes from a mix of the imaginations of architects, dominated by Piano at Daimler Chrysler. This place moves at walking pace.

Time will be frozen in Grassi's new Berlin. Ponderous, authoritarian, empty of any promise, social or scientific, this city his part of the city is constructed in defense against a future threat of consumption and speculation. Grassi seeks to bring permanence and unambiguous clarity to civic order. Here the citizen is both subject and object, secure and controlled. It is this slow speed and avoidance of the deceptions of progress, that could bring such a reality into conflict Berlin's re-emergence as a national capital. Does the denial of speculation in the fabric and organic evolution of the city in some way inhibit the ambitions of the enter prises that choose to perform there? Can Berlin be both Washington and New York? The emerging power of Asia, unfettered by a history of idealized reality, is creating complex and demanding forms of urban assembly, which fuel the economy and stimulate the formation of new products The new Berlin cannot be closed to such a future.

The Bundestag and the Spreebogen Competition

On 20 June 1991 the Bundestag resolved to move the seat of parliament and the core func tions of government from Bonn to Berlin. In 1992 the 'Spreebogen International Competition for Design Ideas' was announced. Eight hundred and thirty-five entries were received from across the world, presenting a revealing slice through global imagination and desire. The task was to give form to the character of German liberal democracy.

In introducing the winners Rita Susmuth, President of the Bundestag, wrote:

The German Bundestag wants to meet the demand for a transparent and efficient parlia ment which is close to its citizenry, is open to the outside, and is conceived as a place of integration and as a center of our democracy At the same time it strives to reunite the city halves, divided for decades in a new spatial and structural order, and thus restore its social and urban identity

Eb Diepgen, Mayor of Berlin, responded:

The present challenge also entails finding proportions of a naturally human scale [and creating] urban space which can bestow identity on a city torn in half for so long, provide a sense of trust and grant a feeling of well-being…all of this remains to be accomplished within this decade and not in some distant Utopia…whoever tries to console us with promises of a distant future does wrong. For many in the East of Germany such a delay would mean relegating their lives to a provisional status

The major instructions for the competition were explicit and established the basic criteria by which the work was judged. The architecture of the proposals should be inte grated with the existing city fabric. Entrants should concentrate on plans which would bring the two halves of the city together, with new spatial axes to enhance the connections. The banks of the Spree should be developed as a place for public use. The Bundesrat (Federal Council) should sit facing the Reichstag with the new offices of the Bundestag closely attached to the north. The position of the other institutions -the German Press Club, the German Parliamentary Society and, most importantly the Federal Chancellery was left to the invention of the entrants.

At that time in Berlin there much concern with the loss of reality. So much lost in the war was doubly lost by the displacement of Modernism and its abstraction of reality. Without extremes of political order, an un-idealized reality seemed to become more desirable. This in hindsight offers one possible measure for understanding the entries, and the evident distrust in the transformative power of architecture. They came from forty-one different countries, including Russia, Saudi Arabia. The result was, in one critic's words, 'a Babylonian jumble of idioms, styles and statements'. There was a distinct difference in the mannerisms of the French and Italian entries. Most of the US entries were quite anonymous, although some shared an interest in the then fashionable strategy of deconstruction. There were a few eccentricities, one proposing rebuilding a section through Hitler's great dome, another offering a flower garden to symbolize the essential humanism of the German character. Otherwise the projects were for the most part uniformly dull; there were few attempts at parody or irony, no proposals objecting to bring political power back to Berlin, no reflections on the dreadful history of this place, neither flamboyant historicism nor Postmodern excess, nor, surprisingly much idealism. And certainly no grand sense of the future. What emerges is a sense that the architects submitted much more in the hope of winning than in offering provocative visions. Many submissions were limited both by an ignorance of Berlin and the workings of the German Government.

The Axel Schultes submission was, by a clear majority of the jury, placed first. It seemed to achieve what Rita Sussmith, President of the Bundestag, called a transparent and efficient Parliament close to the citizenry -open to the outside, conceived as a place of integration and as a center and workshop of our democracy. Schultes had not only practiced for many years in Berlin but had built within the parliamentary district of Bonn The essence of his master plan was to place all the new institutions of government within a hundred-meter-wide band running from the district of Moab it in formerly West Berlin to the Friedrichstrasse Bahnhof formerly in East Berlin. This to become a symbolic physical bridge be tween East and West, embedded in the fabric of the city at each end and, yet, for all its power, deferring to the Reichstag at the center. It would become a spatial and ritual gathering framed by the institutions of government forging a new association between the government and the governed.

At its center, Schultes proposed constructing 'The Nation's Forum,' to be placed exactly over the grand staircase that would have led to Hitler's Grosse Halle. In his imagination the Schultes resurrects the vast flight of stairs is and then fragments it by the many paths into the Forum. The individual on this disturbed stage would rise above the public square and be at one with the center of power. In Schultes' words:

The Forum would be the real heart of Spreebogen, a social powerhouse, a garden of truth, a place for solidarity and protest, a social observatory for those who want to cure themselves of the disease of being German ...The great stairway to the stars, one hundred steps reaching beyond the obligatory cafes, restaurants, bistros; beyond the shops, cinemas and lecture theatres; beyond the escalators burrowing down into the Metro. . Is an attempt to reach the child in every citizen. Maybe in this way the Forum could become a place of euphoric energy and -I wish this were German, too -a place of civil courage.

The general character of the Schultes proposal in many ways resembles Washington DC. The Reichstag in place of the Capitol would look down on a sweeping (albeit one-sided) mall, not to the Washington monument, but to the circular inner court of the Bundesrat. On the north, within the wall of buildings, not quite in the place of the White House, would have been the Chancellery. The location of the Chancellery immediately caused concern to those who felt, perhaps with the White House in mind, that the home of the nation's chief executive should be given a clearer symbolic presence than the Schultes plan allowed. Schultes was personally encouraged by Chancellor Kohl to redesign the Chancellery to make it more fitting for a German White House, and for a Chancellor who is first servant of the state. The led subsequently and unfortunately to a grossly inflated building who presence confused the symbolic intention of the singular formed from different elements and the Nations Forum has remained in limbo.

While the vision was clear Schultes wrote:

The city is sustained: the park, in generous contrast, is given space in a landscape across the two bends in the Spree. The Federation, the third member of the group, is the distinguished one, the special element that links city and country.

The missing link is the city gestalt. The Federation is taken literally as the alliance of the places of the constitution, the meeting place, the discipline of politics as an event for the good of all.

Though Schultes has argued that the metaphysical and the symbolic 'are only allowed in through the back door' of this project, the compelling force of both 'bridge' and 'forum' strongly sug gests otherwise. Schultes has been deeply critical of Berlin's program of competitions, particularly the multiple plans for Potsdamerplatz. He calls them grand projects and writes that:

It is not merely the initiated who are experi encing a dawning awareness that, after the Utopian visions of the thirties, the destruction of the forties, and the obstruction of the sixties, the nineties have brought the wasting disease -the fourth twilight of the city in the space of a century.

He views them as euphemisms of reality, bour geois dressings over monstrous wounds. His vivid prose creates problems. How, for example, to reconcile the plan for Spreebogen with his assertion that 'shamefully, the only way to demonstrate the State to the German nation is to veil a monument in a cloak of vanity'? The master plan sees the city interfering with the institutions of government, both as structure and perform ance, to constrain the selfishness of power. However the hard, axial authority of the plan is in marked contrast to the poignant attempts at informality in Hans Scharoun's city plans of 1957, which also sought an order that would limit power. The test for the Schultes master plan was in its transla tion by the unpredictable architects chosen by competition to develop it. The test for the building committees of the Bundestag was their willingness -or ability -to sustain support for an instrument of government that is so complex and uncertain in its political content. (Schultes is able to create works of great formal strength, yet unlike Libeskind and others, his work and his imagination has little affect outside of Germany.)

The results are mixed, the continuous wall of administration buildings north of the Reichstag , though not by Schultes conforms exactly to the master plan, and continues its ordered path across the Spree. The architecture is tasteful yet characterless. Much more problematic is the Schultes house for the Chancellor. First impressions are disturbed by a forecourt dominated by a set of large freestanding white columns each of which inexplicably, supports a large tree high above the ground. Schultes is able to create powerful elegiac forms, and the mass of the house has presence, yet no clear identity. Looking more corporate the stately as one enters the grand foyer. The effect of the plan which is centered on a generous spiraling stair is of restless and anonymous spaces. Chancellor Schroeder, who followed Kohl, was public inn his dislike for the building mentioning that despite its size there was only one bedroom and his children ended up sleeping in the kitchen. By such is are dreams diminished.

The Reichstag

Late in 1992 a small group of architects was chosen to develop proposals for the rehabilitation of the Reichstag. The Reichstag had been completed in 1894 to the plans of the architect Paul Wallot, on the east side of the Konigsplatz, a nineteenth century military exercise field. From the turn of the century there was much discussion about transforming Konigsplatz into a 'forum for the nation.' In 1912 Otto March proposed making it a patriotic forum by placing the Royal Opera House opposite the Reichstag. In 1915, in midst of a war that German believed it would win, Felix Wolf argued for the creation of a German Forum to be dominated by a pan theon for fallen heroes. At the end of the war a different shape of romanticism emerged with Otto Kohtz' proposal that the new democratic government be housed in a pyramiding skyscraper; and in the twenties Konigsplatz became the Platz der Republik.

More rational than Kohtz but equally progressive was the project by Martin Machler, which sought to represent democratic government with buildings formed by what he called 'systematic bundling' a new order directly linked to rail terminals and new road systems. Machler's work stimulated political structures from Haring, Poelzig and Hilberseimer all of which were displayed in the building exhibition of 1927. Haring's proposal by 1929 included the construction of a grand vaulted tribune, another 'Forum of the People' that was meant to opposed and diminished the power of the Reichstag. Such giddy dreams, however, came to a dramatic end in February,1933 when the Reichstag was burned to consolidate Hitler's authority, and the Platz der Republik became, once again, Konigsplatz.

By the end of the thirties, under the direction of Albert Speer, plans were being prepared to transform Berlin into the capital of Germania. Immediately north of the Reichstag, at the end of a great north-south axis that would have cut through the city, Hitler began to construct the Grosse Halle to overwhelm both the Capitol in Washington and St Peter's in Rome. It was conceiver to become the political and spiritual focus of the world. The force necessary to destroy Hitler, devastated the city, a tragically ruined Reichstag at the center. Hans Schar oun was appointed Urban Development Director for Berlin in May 1945 and remained the city's Architecture Commissioner for the next twenty years He wrote in 1946:

What remained after the air raids and the final struggle have reduced the density of develop ment and ripped apart the urban fabric. This offered the material for creating a new urban landscape and for giving order to the frag mentary and un-proportioned in the same way that forest, meadow, mountain and lake work together in a beautiful landscape.

Grand dreams, but in the increasingly divided city there was no clarity to build anything. The wall creating two cities ran immediately behind the Reichstag.

The task was to renovate the Reichstag into the plenary chamber of the Bundestag. The Reichstag had been partially restored after the war, and from the mid-sixties, it was used by Bonn for occa sional parliamentary sessions, a symbolic demonstration of the West German political presence in Berlin. The competition called for the creation of a transparent and efficient parlia ment, close to its citizenry. Beyond function the central issue was political symbolism. This competition was limited to a small number of invitees, and all finalist submissions came from non Germans. There never explained or excused but a German expression of power in this most conflicted place still remained difficult.

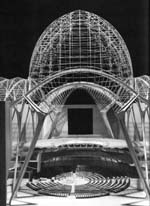

Three projects were initially placed first equal; Pi de Bruijn, Santiago Calatrava, and Norman Foster. Each gave very different readings of power. Pi de Bruijn, of the Amsterdam group de Architekten Cie, offered a solution reminiscent of a provincial Brasilia, in which the chamber emerges from a podium in front of the Reichstag as a large bowl. The theatrics were completed by a screen wall to the north which both respected yet diminished the Reichstag. In contrast, Spanish engineer and architect Santiago Calatrava would have completely rebuilt the Reichstag's interior as a crystal palace, re-establishing and enlarging the dome as an intersection of four glass segmental shells floating above the plenary hall. The shells could also open like the petals of a flower, open the center of power the air transforming the dome and the symbol into a benign expression of openness in government canceling the painful memories of history.

After deliberation the third finalist, the English architect Norman Foster, was chosen first among equals. His entry would have enclosed the Reichstag under a vast horizontal canopy, neutralizing its historical presence, the Reichstag in aspic. Within the shell of the old building the new chamber was to be housed in a vast transparent hall, a physical representation of the transparency of democracy and the cleansing of the past.

As the Schultes master plan began to translate into architecture, a dramatic change took place in the form of the Reichstag. The building committee rejected the central concept of Foster's winning scheme, a self-effacing and neutralizing canopy that would have diminished the presence of the historic building. Foster was asked to rethink and dutifully removed the canopy and the design was reduced to a glass case sitting within the existing shell. Even in the photographs of the model, it is an uncertain thing without strong presence. In the latter half of 1994 Foster was asked to think again particularly how to re-establish the central authority Reichstag with the new landscape of the Bundestag. He responded by creating a great glass dome covering a vast reflecting mirror, which he likened to the lighthouse of the nation. In this confused affair, the Calatrava creation of the grand four-segment dome which could have, on appropriate occasions, open like the petals of a flower, totally undermin ing and transforming this symbol of power, was lost. Yet it was the Calatrava dome that forced Foster's imagination to create a structure avoiding any reference to the work of his competitor. (Foster like Libeskind and Eisenman is able to conceive of objects that satisfy a world imagination equally at appropriate to Berlin as to Shanghai and even New York, yet unlike his colleagues he gains his influence through reason rather than emotion.)

Setting the dispute aside the completed work has exceeded expectations both as a debating chamber and as a national even world symbol. Visiting the glass hemisphere has become a ritual for every tourist in the city; lining up early for the experience of spiraling through space in the soft morning light, at the power center of the nation. .To rebuild a ruin whose tragic image was for decades a continual reminder of the most dreadful events in the nation's history, such that it instantly sheds its past to become a beacon for the future, is a brilliant achievement.

» back to top

» back to top